Our History

As part of the celebrations for our 125th anniversary in 2023, we delved into the archives to illustrate some key moments in the school’s history.

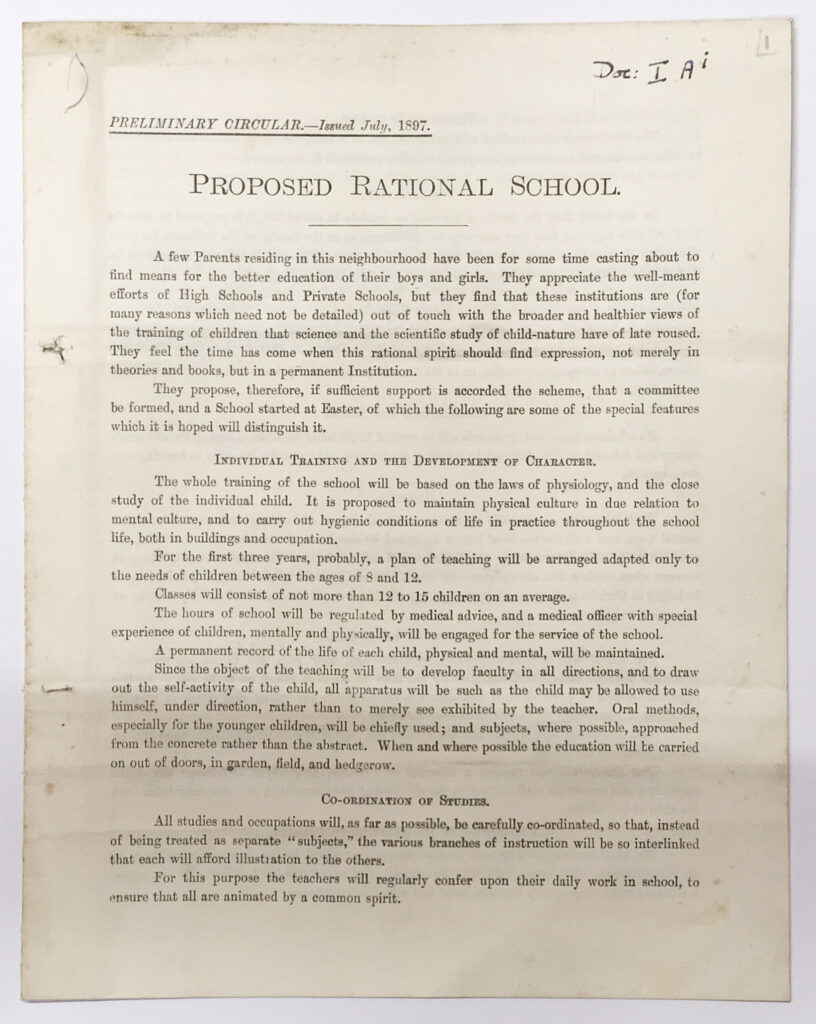

Proposal For A New School

Proposal For A New School

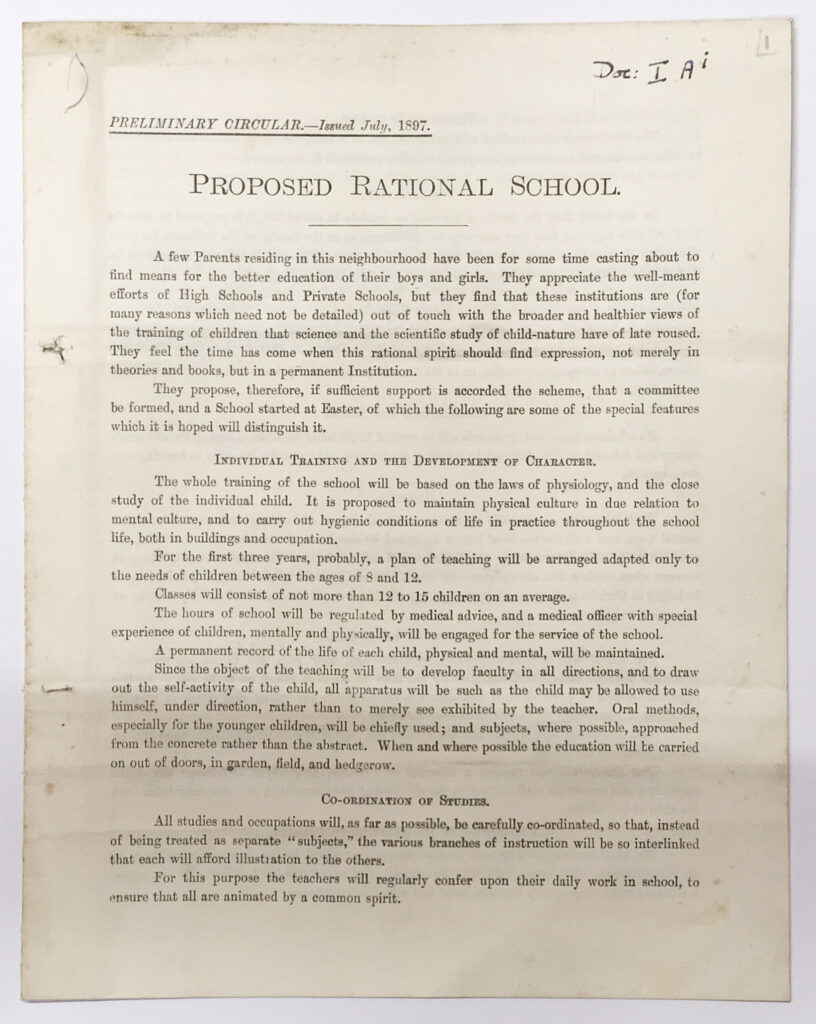

We begin our look at the history of KAS in 125 Artefacts with the document which started it all.

This is the original 1897 ‘Proposed Rational School’ circular setting out the vision and ethos essential to The King Alfred School’s approach to education.

As a school, KAS retains many of the core values set out in this document today.

As an example our current 6-8 curriculum, which includes interdisciplinary learning as a core element, could be described perfectly by the words in this original proposal for the school in 1897: “All studies and occupations will, as far as possible, be carefully co-ordinated, so that, instead of being treated as separate “subjects,” the various branches of instruction will be so interlinked that each will afford illustration to the others.”

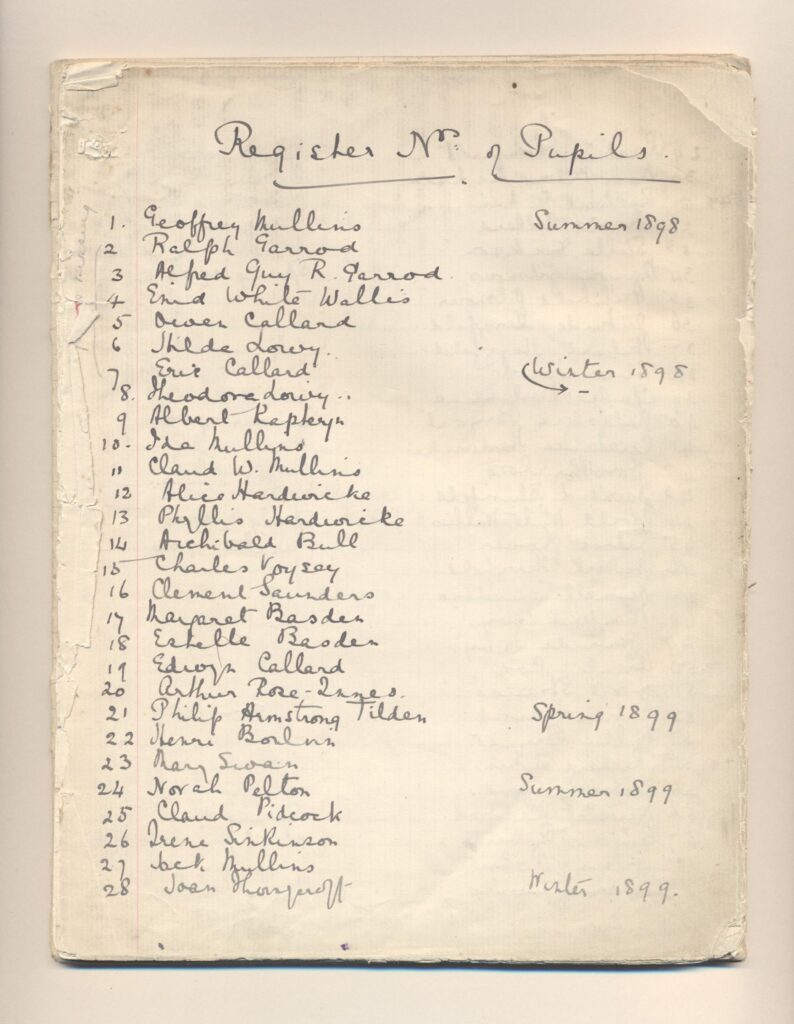

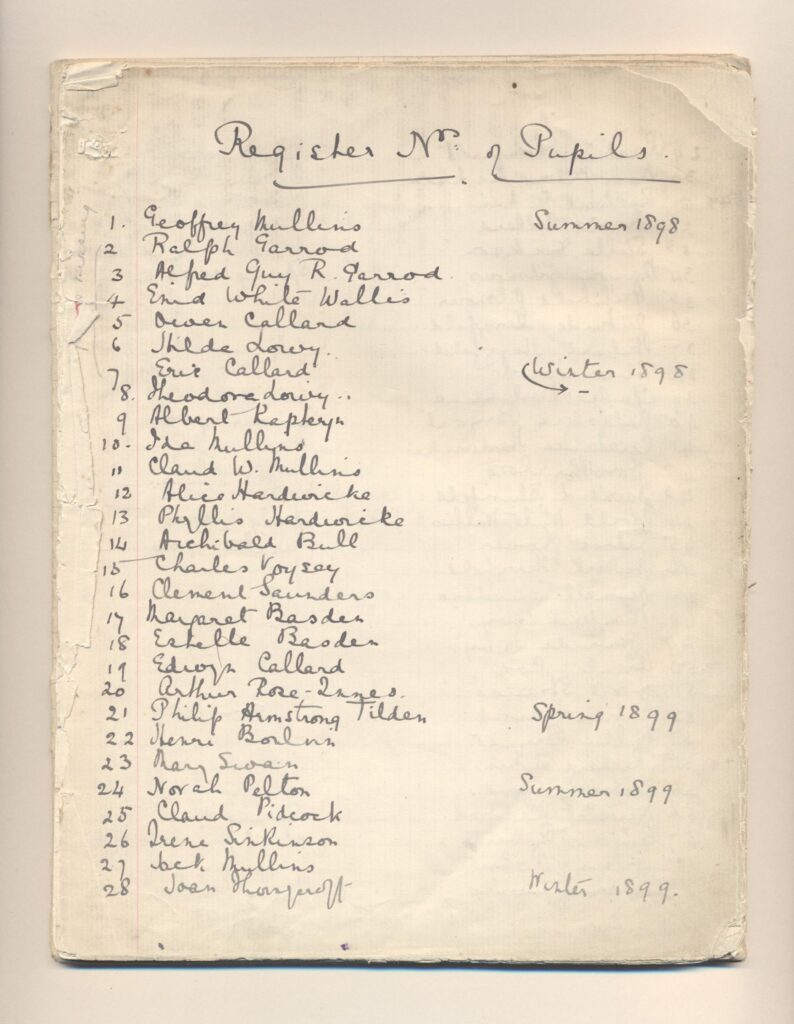

The First Register

The First Register

The King Alfred School opened 24 June 1898. Women’s suffrage campaigner Millicent Fawcett, founder of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), took part in the inaugural ceremony.

The first register lists seven pupils, five boys and two girls, aged seven to nine.

The school stood out as it was coeducational, with girls and boys learning together, from the start. This commitment to gender equality may have been part of why reform minded people such as Fawcett took an interest in the new school.

The First Head

The First Head

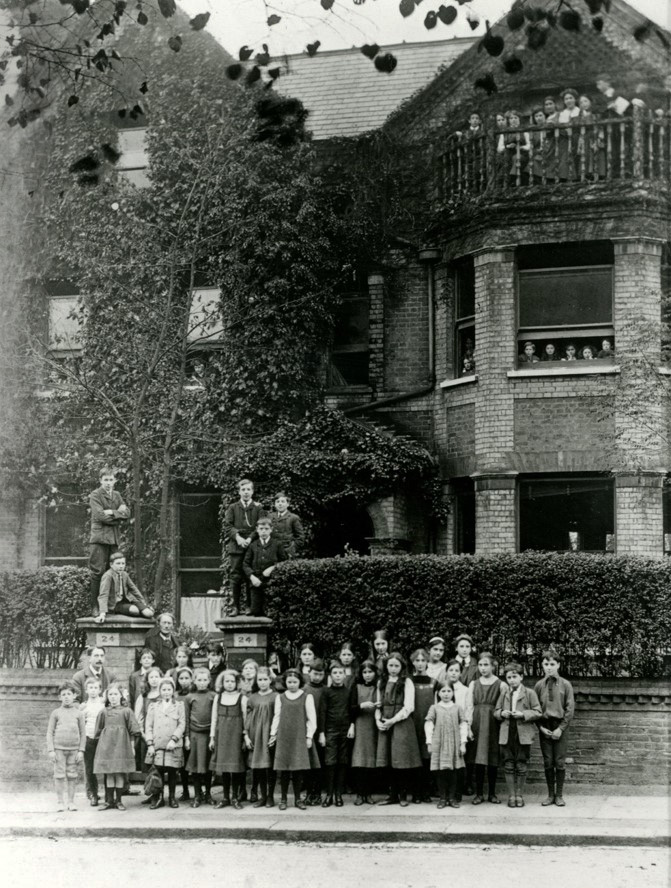

The King Alfred School’s first Headmaster Charles E Rice is shown here with students circa 1899. Rice came to KAS from Bedales, where he served as assistant master and taught science plus a diversity of subjects ranging from English to Woodwork. His experience applying exploratory, experiential and experimental educational practices was well suited to KAS’s ethos.

Rice was tasked with delivering the progressive framework for “Educational Science” devised by the King Alfred School Society (KASS) in collaboration with leading educationalist Joseph John Findlay. The resulting curriculum met the learning needs of students in an age of change leading up to the turn of the century. It also remained true to the founders’ vision of a happy, child centered approach to education.

Proposal For A New School

We begin our look at the history of KAS in 125 Artefacts with the document which started it all.

This is the original 1897 ‘Proposed Rational School’ circular setting out the vision and ethos essential to The King Alfred School’s approach to education.

As a school, KAS retains many of the core values set out in this document today.

As an example our current 6-8 curriculum, which includes interdisciplinary learning as a core element, could be described perfectly by the words in this original proposal for the school in 1897: “All studies and occupations will, as far as possible, be carefully co-ordinated, so that, instead of being treated as separate “subjects,” the various branches of instruction will be so interlinked that each will afford illustration to the others.”

The First Register

The King Alfred School opened 24 June 1898. Women’s suffrage campaigner Millicent Fawcett, founder of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), took part in the inaugural ceremony.

The first register lists seven pupils, five boys and two girls, aged seven to nine.

The school stood out as it was coeducational, with girls and boys learning together, from the start. This commitment to gender equality may have been part of why reform minded people such as Fawcett took an interest in the new school.

The First Head

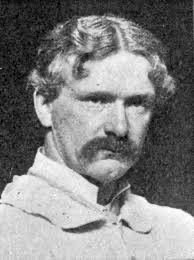

The King Alfred School’s first Headmaster Charles E Rice is shown here with students circa 1899. Rice came to KAS from Bedales, where he served as assistant master and taught science plus a diversity of subjects ranging from English to Woodwork. His experience applying exploratory, experiential and experimental educational practices was well suited to KAS’s ethos.

Rice was tasked with delivering the progressive framework for “Educational Science” devised by the King Alfred School Society (KASS) in collaboration with leading educationalist Joseph John Findlay. The resulting curriculum met the learning needs of students in an age of change leading up to the turn of the century. It also remained true to the founders’ vision of a happy, child centered approach to education.

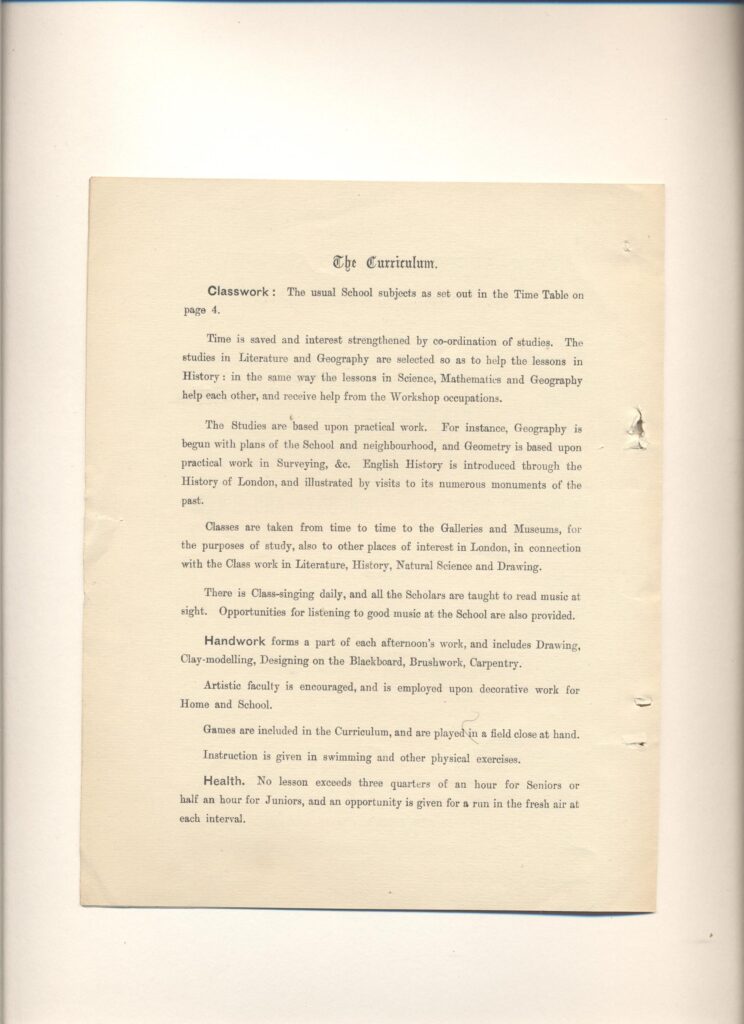

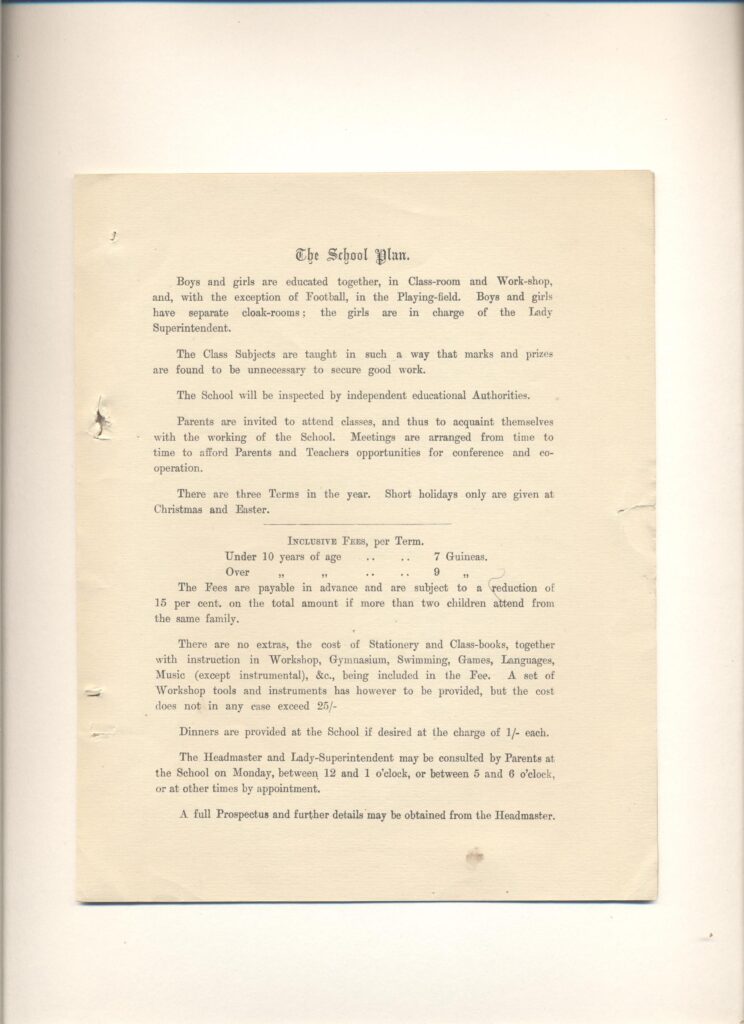

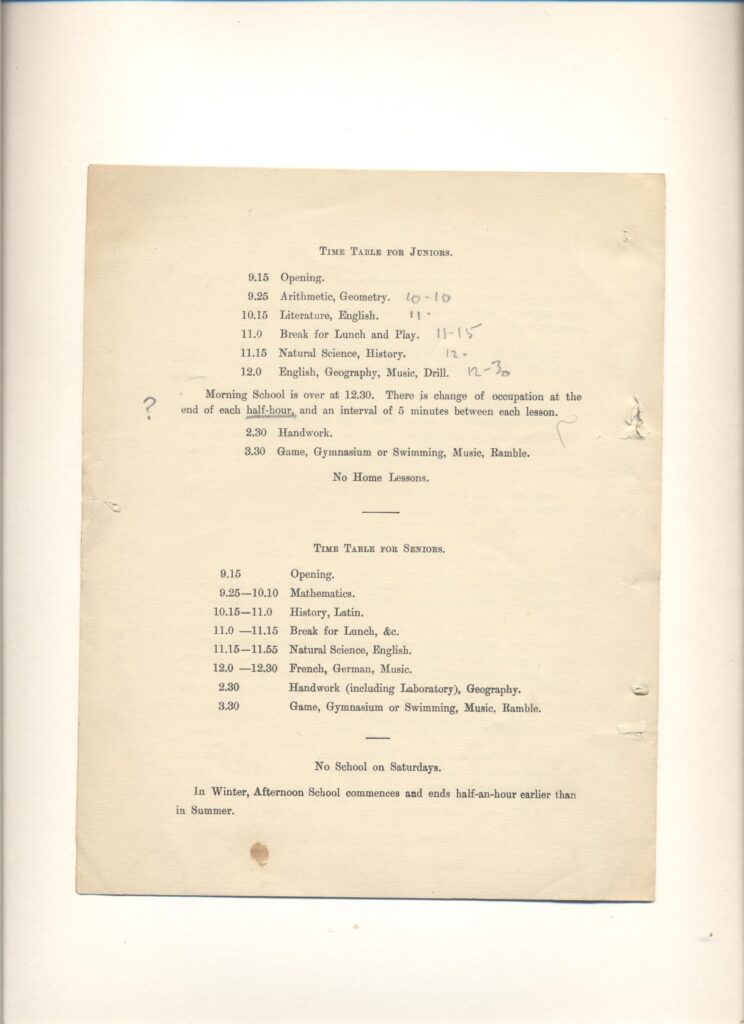

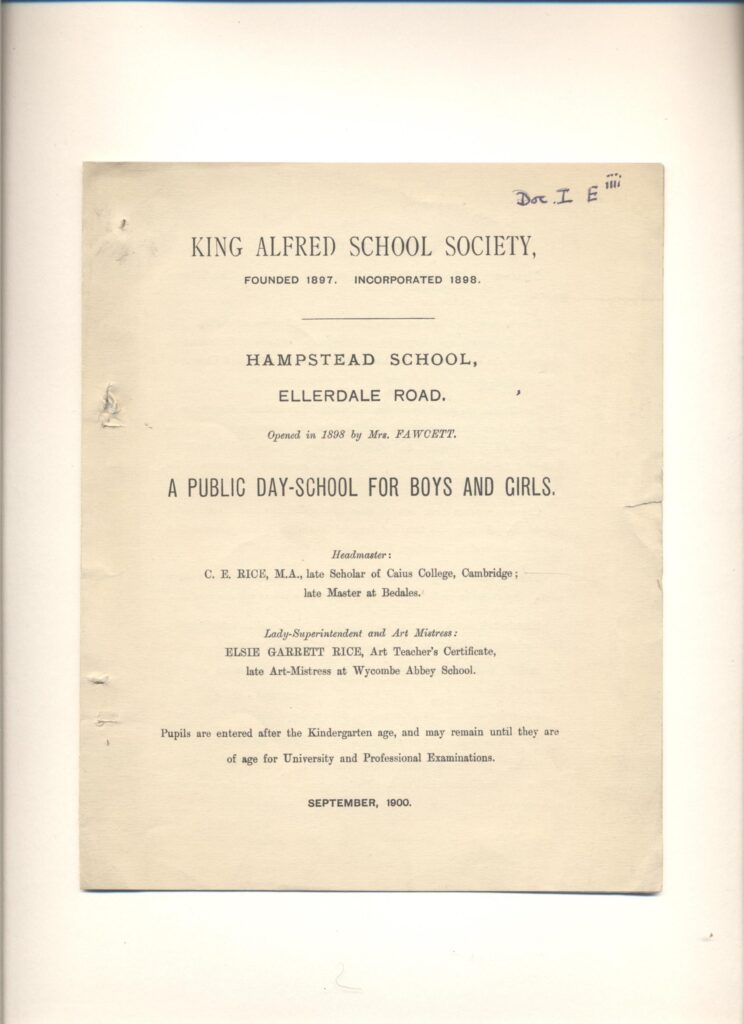

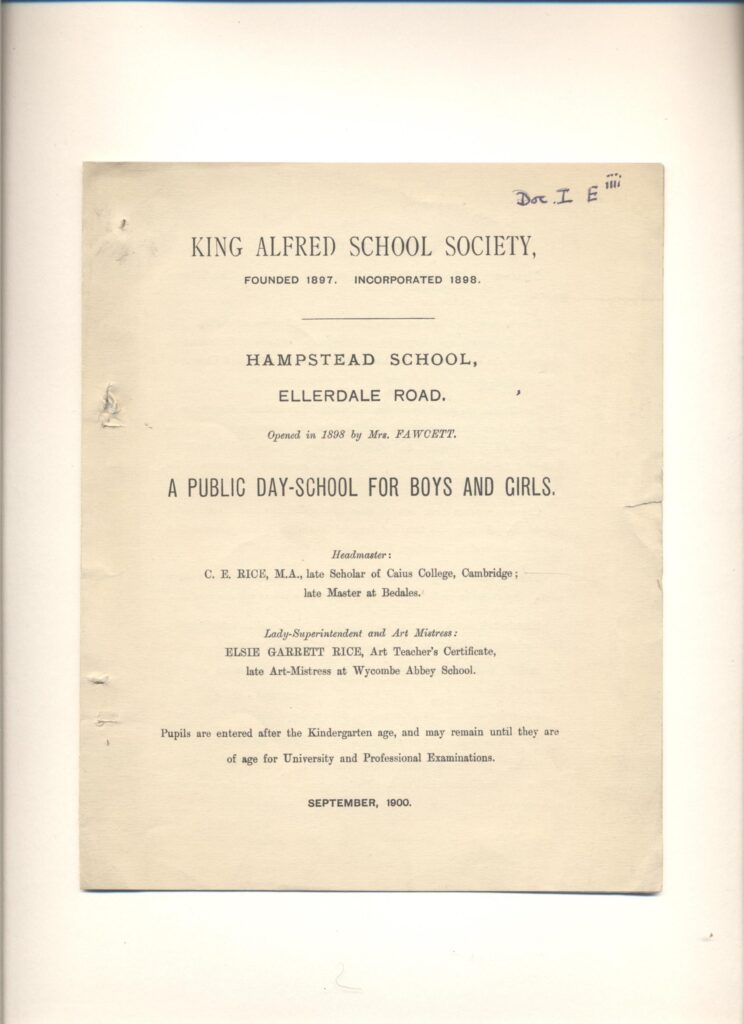

School Prospectus 1900

School Prospectus 1900

The King Alfred School Prospectus for 1900 provides an overview of the educational experience parents and students could expect.

Compare it to our current prospectus here.

Co-ordinated studies was a unique feature approaching traditional subjects from an interdisciplinary perspective. See the timetable on page 4 for a glimpse of a Junior and Senior student’s day at KAS. In Winter, classes ended 30 mins earlier than in Summer. “No Home Lessons” reflects a commitment to family and leisure time outside of school.

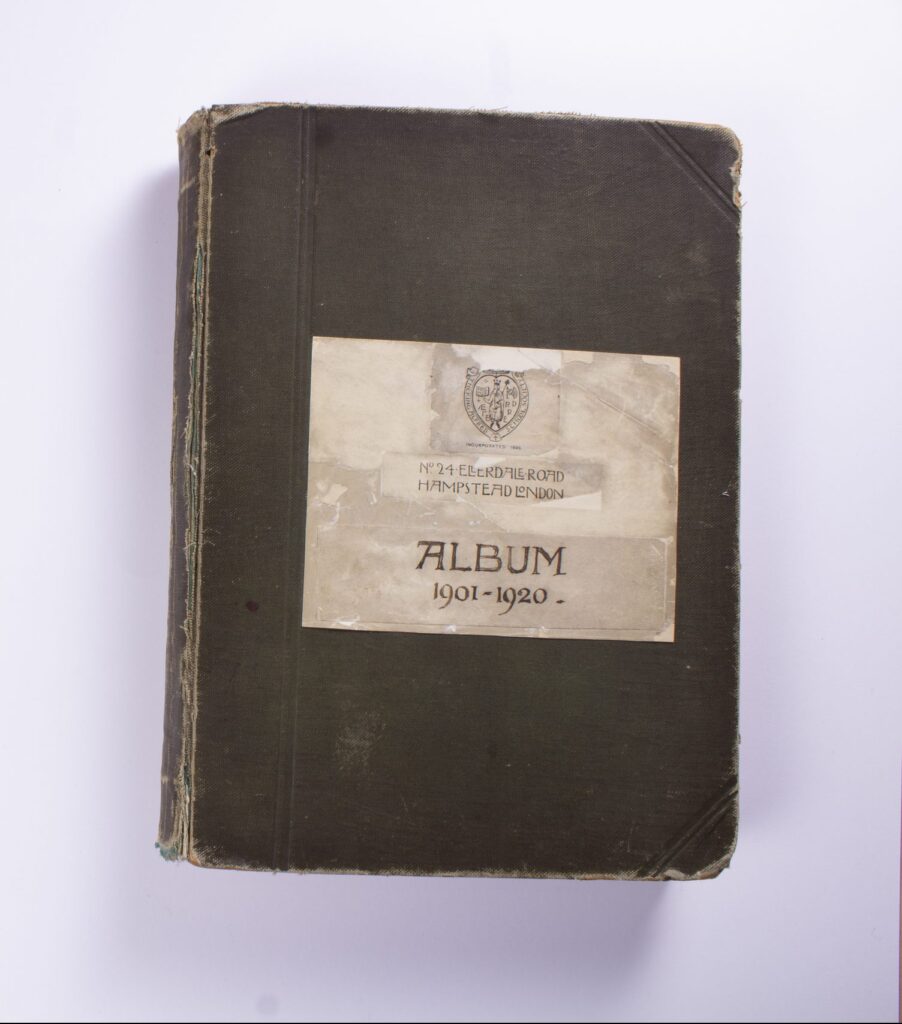

The Russell Album

The Russell Album

When John Russell was appointed KAS headmaster in 1901 he knew he was joining an educational institution that was making history. Russell made it his duty to document the school’s early days – in many ways he was our first archivist. “The Russell Album” shown here captured school life and his place in it from 1901-1920.

Russell embodied the KAS ethos and strove for a balance between providing a progressive, child centered educational experience and meeting traditional measures of academic success including exam results and progression to university. JR, as he was affectionately known, developed a strong bond with his students many of whom continued to correspond with him after graduating. (We have his letters in our collection too!)

The final pages of The Russell Album show Russell in a jolly mood on a boating trip with his students.

The Goat Rope

The Goat Rope

This is exactly what it says it is – a rope used to tie up the school goats when they weren’t allowed to roam the field.

Former students may remember Dulcie, Daisy, Dolly and Billy. The goats roamed the school field and even starred in a pantomime! We no longer have a school goat, but the Lower School Farm remains a vital part of our learning environment.

School Prospectus 1900

The King Alfred School Prospectus for 1900 provides an overview of the educational experience parents and students could expect.

Compare it to our current prospectus here.

Co-ordinated studies was a unique feature approaching traditional subjects from an interdisciplinary perspective. See the timetable on page 4 for a glimpse of a Junior and Senior student’s day at KAS. In Winter, classes ended 30 mins earlier than in Summer. “No Home Lessons” reflects a commitment to family and leisure time outside of school.

The Russell Album

When John Russell was appointed KAS headmaster in 1901 he knew he was joining an educational institution that was making history. Russell made it his duty to document the school’s early days – in many ways he was our first archivist. “The Russell Album” shown here captured school life and his place in it from 1901-1920.

Russell embodied the KAS ethos and strove for a balance between providing a progressive, child centered educational experience and meeting traditional measures of academic success including exam results and progression to university. JR, as he was affectionately known, developed a strong bond with his students many of whom continued to correspond with him after graduating. (We have his letters in our collection too!)

The final pages of The Russell Album show Russell in a jolly mood on a boating trip with his students.

The Goat Rope

This is exactly what it says it is – a rope used to tie up the school goats when they weren’t allowed to roam the field.

Former students may remember Dulcie, Daisy, Dolly and Billy. The goats roamed the school field and even starred in a pantomime! We no longer have a school goat, but the Lower School Farm remains a vital part of our learning environment.

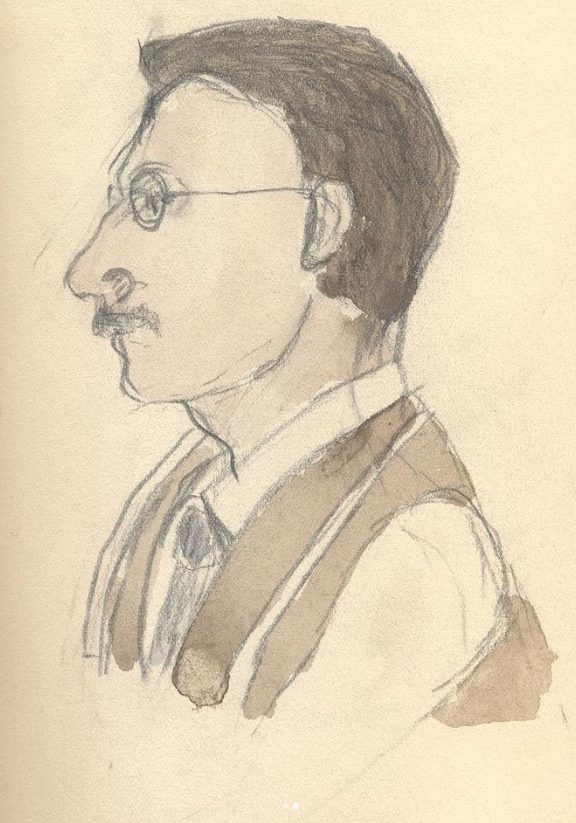

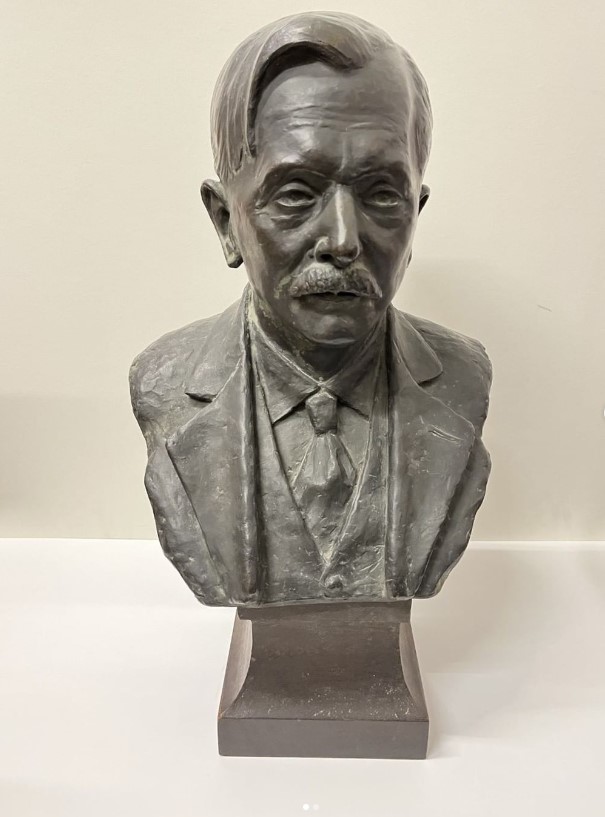

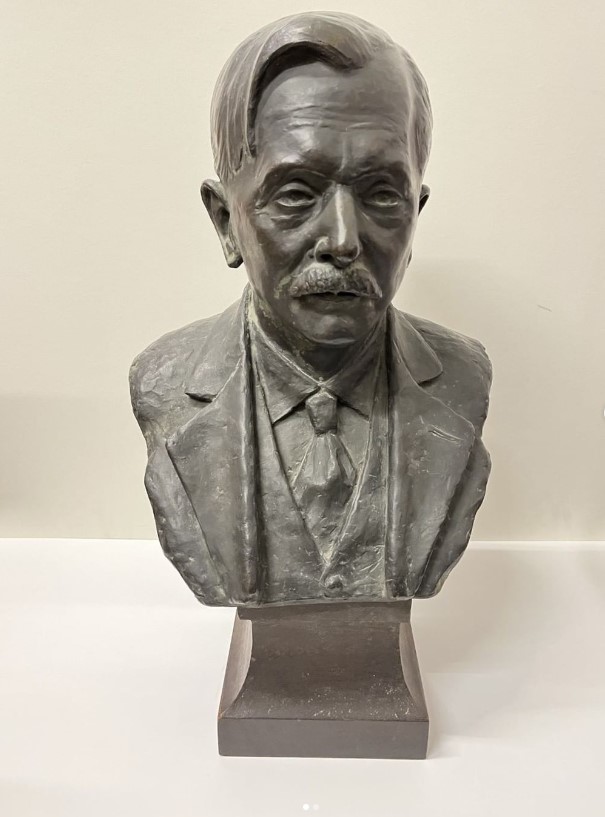

An Inspirational Teacher

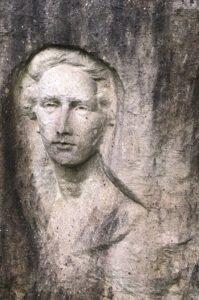

An Inspirational Teacher

The KAS Archives holds more than just documents. This is a bronze bust of George Chester Earle, who joined the school in 1903. Earle was a favourite teacher, known for his interdisciplinary approach mixing English with woodwork and inspiring creative thinking.

Student Rosalind Thornycroft recalled, “Keats and Shakespeare lines flew about with the woodshavings and in his white carpenter’s apron and flashing glasses he actively demonstrated the mystery of spirit and material made one.”

The bust was made by Montenegrin sculptor Yanko Brayovitch shortly after Earle’s death in 1949. It was commissioned by Earle’s partner Eleanor Farjeon, an accomplished author who is best known for her children’s literature and for writing the hymn “Morning has Broken.” Earle’s granddaughter donated the beautiful piece to our collection.

The archive also holds this charming student sketch of Earle, which echoes the features captured in Brayovitch’s sculpture.

Early School Magazines

Early School Magazines

King Alfred School has a long tradition of student produced magazines. The first editions were hand written and contained original illustrations. The pages were bound into an annual, the only copy of which was kept by the headmaster. This is a cover from 1901 showing a beautiful illustration with echos of Charles Rennie Mackintosh.

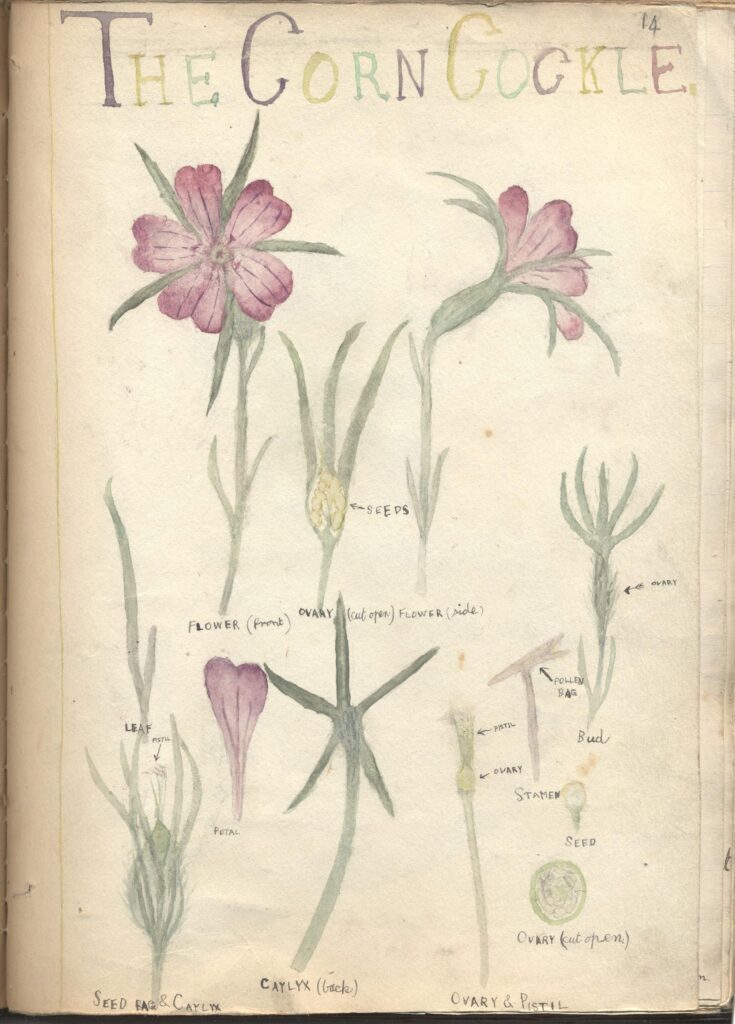

Here is another nature-inspired illustration from inside the 1899 magazine by Mary Swan:

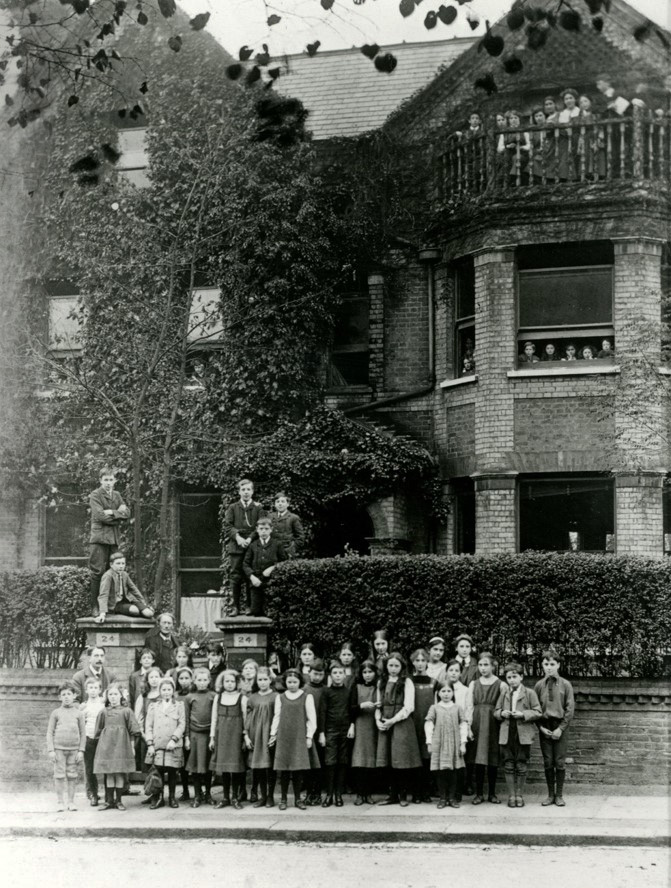

The First School Building

The First School Building

This fantastic photo is of 24 Ellerdale Road, Hampstead – the original school site. With students and teachers gathered outside it shows the smaller size of the school in it’s early days.

Sheila, our KAS Archivist got on her bike to check it out, taking historic photos for identifying purposes!

This image shows students circa 1909 pouring out of the building with Headmaster John Russell posed casually on the right. In 1910 KAS expanded into the adjacent house.

Although the building has been modernised, it bears a striking resemblance to the place KAS once called home.

An Inspirational Teacher

The KAS Archives holds more than just documents. This is a bronze bust of George Chester Earle, who joined the school in 1903. Earle was a favourite teacher, known for his interdisciplinary approach mixing English with woodwork and inspiring creative thinking.

Student Rosalind Thornycroft recalled, “Keats and Shakespeare lines flew about with the woodshavings and in his white carpenter’s apron and flashing glasses he actively demonstrated the mystery of spirit and material made one.”

The bust was made by Montenegrin sculptor Yanko Brayovitch shortly after Earle’s death in 1949. It was commissioned by Earle’s partner Eleanor Farjeon, an accomplished author who is best known for her children’s literature and for writing the hymn “Morning has Broken.” Earle’s granddaughter donated the beautiful piece to our collection.

The archive also holds this charming student sketch of Earle, which echoes the features captured in Brayovitch’s sculpture.

Early School Magazines

King Alfred School has a long tradition of student produced magazines. The first editions were hand written and contained original illustrations. The pages were bound into an annual, the only copy of which was kept by the headmaster. This is a cover from 1901 showing a beautiful illustration with echos of Charles Rennie Mackintosh.

Here is another nature-inspired illustration from inside the 1899 magazine by Mary Swan:

The First School Building

This fantastic photo is of 24 Ellerdale Road, Hampstead – the original school site. With students and teachers gathered outside it shows the smaller size of the school in it’s early days.

Sheila, our KAS Archivist got on her bike to check it out, taking historic photos for identifying purposes!

This image shows students circa 1909 pouring out of the building with Headmaster John Russell posed casually on the right. In 1910 KAS expanded into the adjacent house.

Although the building has been modernised, it bears a striking resemblance to the place KAS once called home.

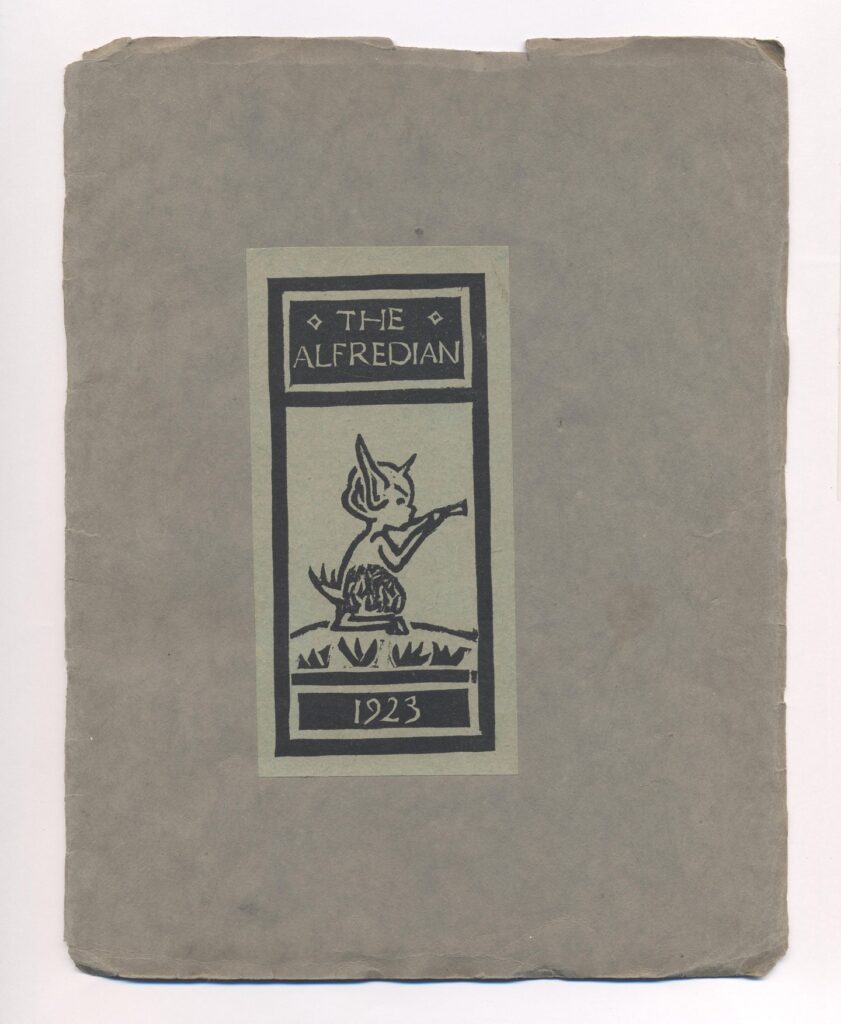

The Alfredian Magazine

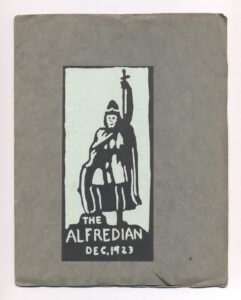

The Alfredian Magazine

In 1923 The KAS Magazine was relaunched as “The Alfredian” with beautifully printed covers. The covers and pages were produced on-site in The KAS Print Room.

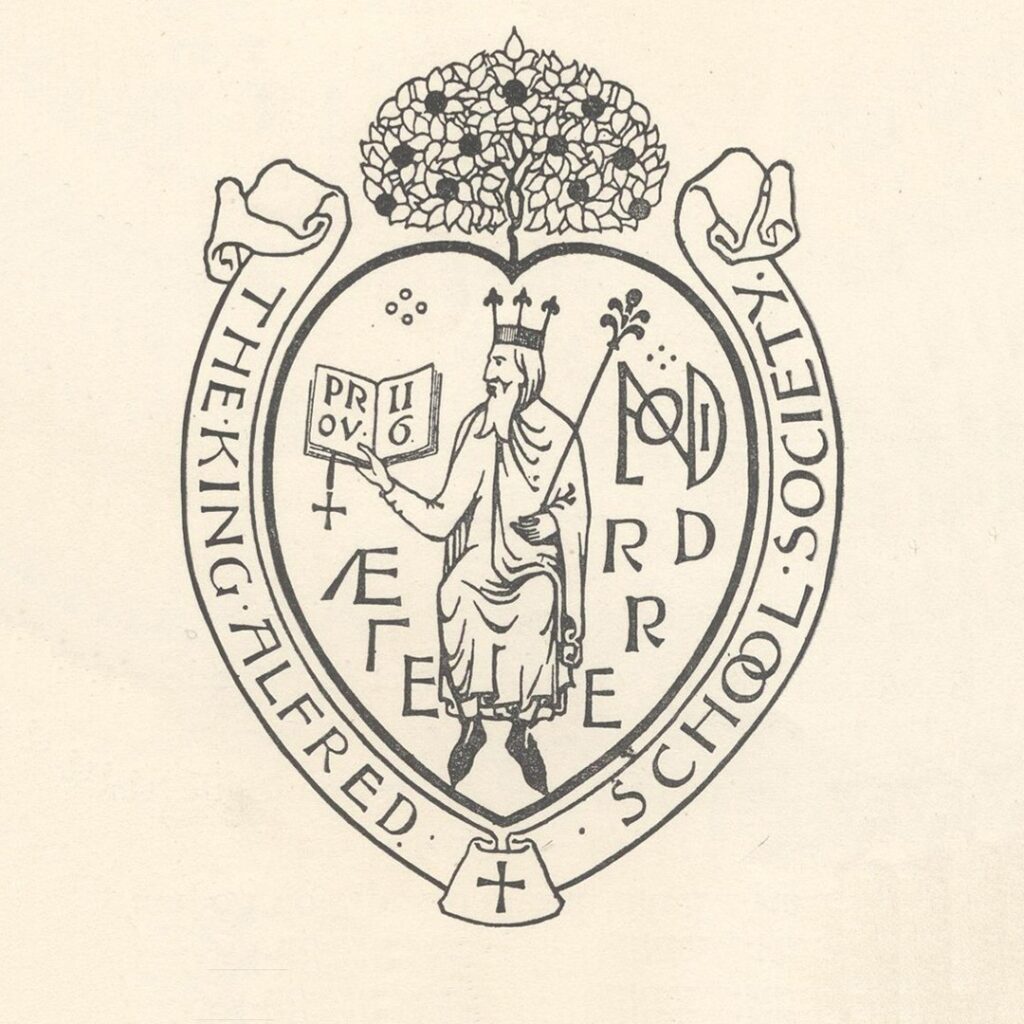

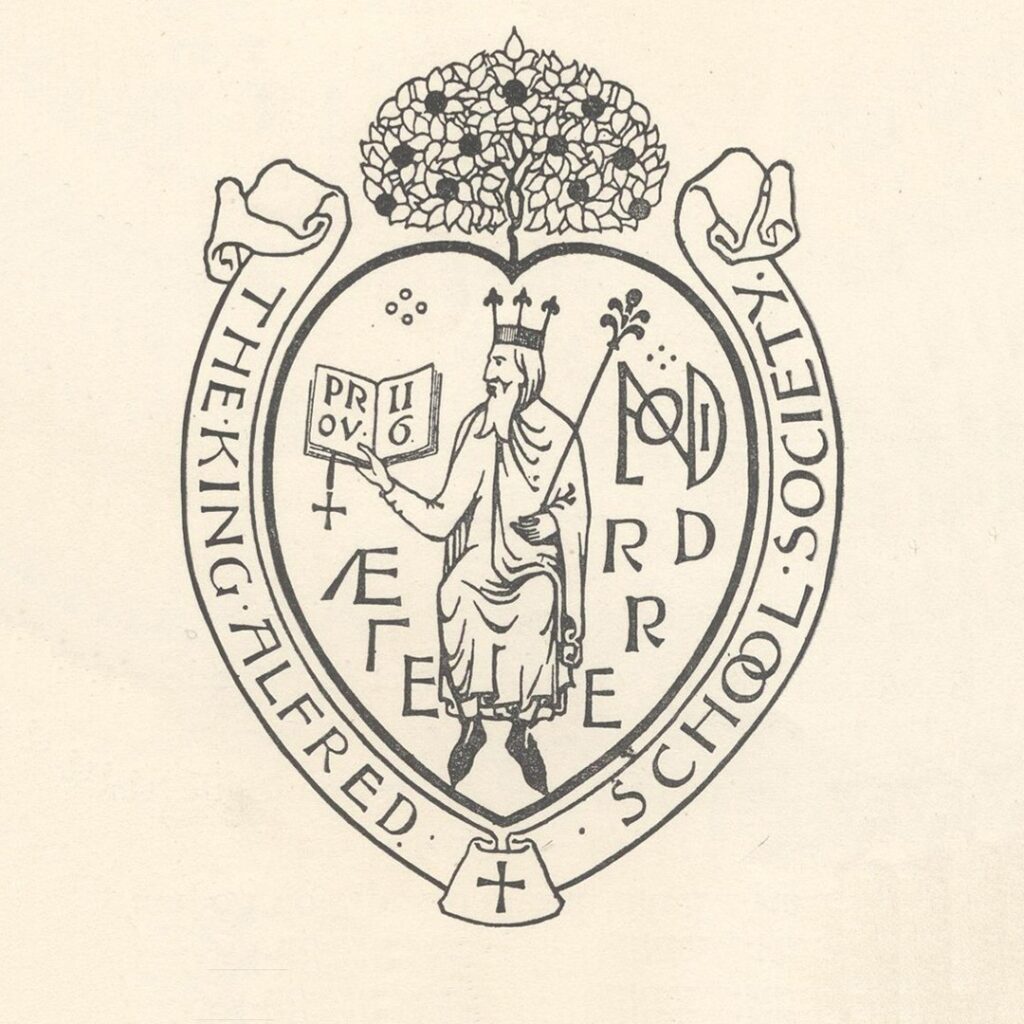

The School Crest

The School Crest

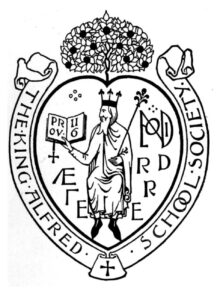

Architect and designer CFA Voysey designed the King Alfred School crest in 1898. King Alfred the Great appears in a heart with the tree of knowledge springing from it. The initials surrounding Alfred were used on the coins of his day. He holds a bible open to Proverbs II:6, “For the Lord giveth wisdom. Out of his mouth comes knowledge and understanding.”

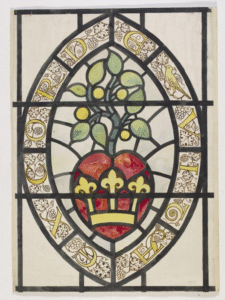

Voysey later simplified the design to show Alfred’s stylised crown enclosed in a heart sprouting a sapling and including the motto “Ex Corde Vita”, out of the heart springs life. The V&A holds the design for an arts and crafts style stained glass window in this pattern dated 1907 and signed by Voysey.

Voysey’s children attended KAS. He designed several buildings for KAS which were never built but inspired the school’s architectural vision.

The Garden School

The Garden School

In May 1910, KAS opened its first Garden School for pre-school and reception age children.

The prospectus noted “All work and play is carried out either in the open meadow or under shady trees, but for use in inclement weather there is a shelter, the whole front of which can be thrown open to the south.”

The approach of the new school emphasized play and self-directed learning as essential to child development.

A report by the Chief Medical Officer of the Board of Education noted that the open-air environment “stimulated mental alertness” and eliminating epidemics and infectious disease among staff or students.

The Alfredian Magazine

In 1923 The KAS Magazine was relaunched as “The Alfredian” with beautifully printed covers. The covers and pages were produced on-site in The KAS Print Room.

The School Crest

Architect and designer CFA Voysey designed the King Alfred School crest in 1898. King Alfred the Great appears in a heart with the tree of knowledge springing from it. The initials surrounding Alfred were used on the coins of his day. He holds a bible open to Proverbs II:6, “For the Lord giveth wisdom. Out of his mouth comes knowledge and understanding.”

Voysey later simplified the design to show Alfred’s stylised crown enclosed in a heart sprouting a sapling and including the motto “Ex Corde Vita”, out of the heart springs life. The V&A holds the design for an arts and crafts style stained glass window in this pattern dated 1907 and signed by Voysey.

Voysey’s children attended KAS. He designed several buildings for KAS which were never built but inspired the school’s architectural vision.

The Garden School

In May 1910, KAS opened its first Garden School for pre-school and reception age children.

The prospectus noted “All work and play is carried out either in the open meadow or under shady trees, but for use in inclement weather there is a shelter, the whole front of which can be thrown open to the south.”

The approach of the new school emphasized play and self-directed learning as essential to child development.

A report by the Chief Medical Officer of the Board of Education noted that the open-air environment “stimulated mental alertness” and eliminating epidemics and infectious disease among staff or students.

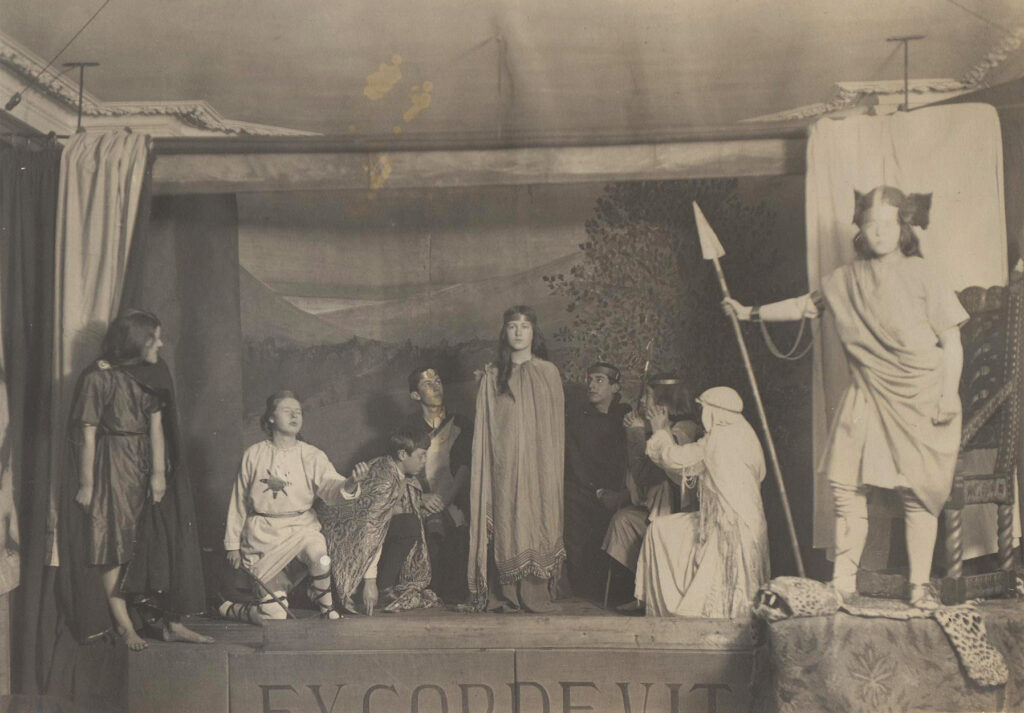

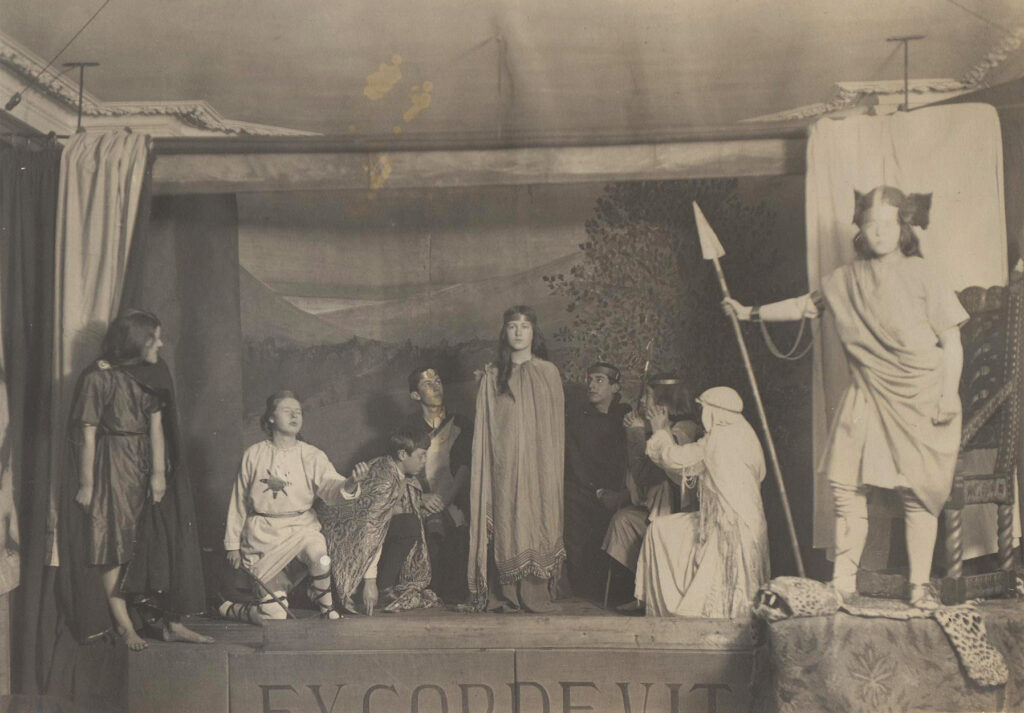

School Play

School Play

Drama and performances have always been a central part of student life at KAS. In 1912, the school play was Odin. If you look carefully, you can see the school motto “Ex Corde Vita” on the stage.

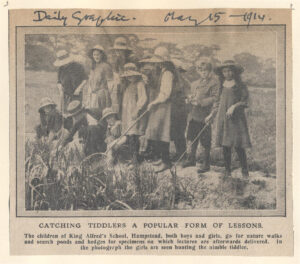

Outdoor Learning

Outdoor Learning

Outdoor learning has always been a central part of the King Alfred School philosophy.

These photographs from 1914 capture children going for nature walks and searching ponds for specimens. After spending time outdoors, they would learn about the they found in lectures.

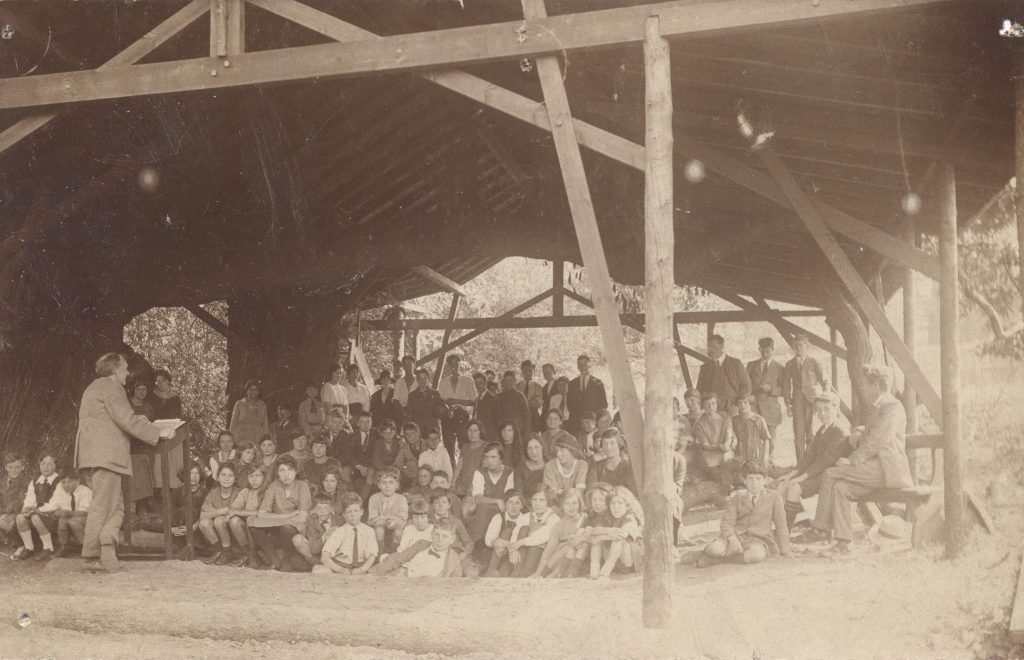

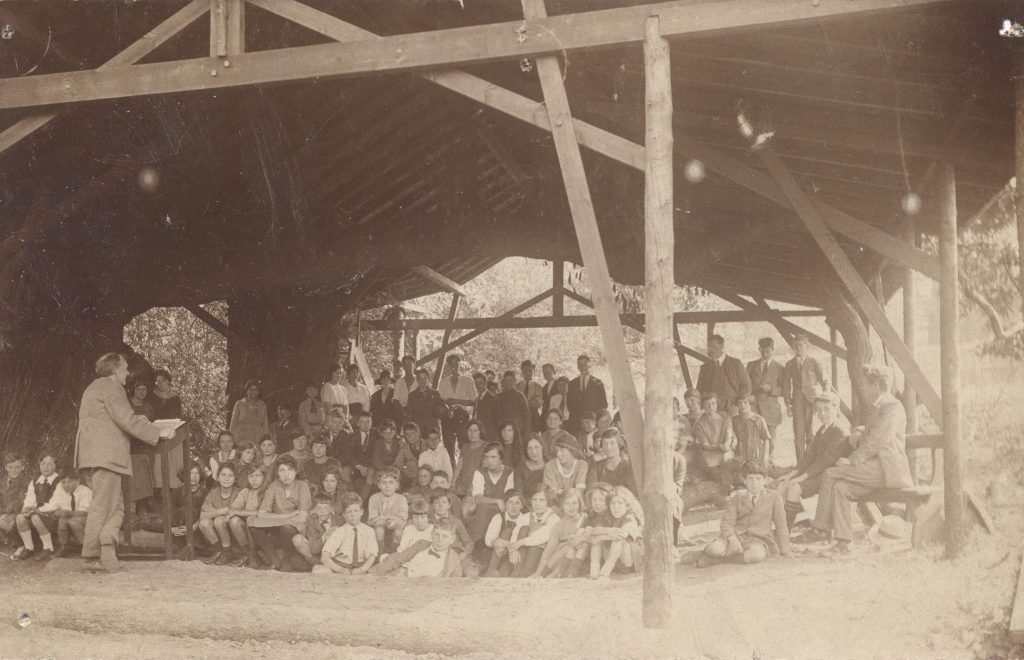

Squirrel Hall

Squirrel Hall

1920 marked the retirement of Headmaster John Russell and the appointment of Joseph Wicksteed.

Wicksteed was committed to the value of open air education. In 1921, one of his first acts as Head was to design and build Squirrel Hall with staff and students. The building had no walls and consisted solely of a wooden roof suspended by tree trunks.

School Play

Drama and performances have always been a central part of student life at KAS. In 1912, the school play was Odin. If you look carefully, you can see the school motto “Ex Corde Vita” on the stage.

Outdoor Learning

Outdoor learning has always been a central part of the King Alfred School philosophy.

These photographs from 1914 capture children going for nature walks and searching ponds for specimens. After spending time outdoors, they would learn about the they found in lectures.

Squirrel Hall

1920 marked the retirement of Headmaster John Russell and the appointment of Joseph Wicksteed.

Wicksteed was committed to the value of open air education. In 1921, one of his first acts as Head was to design and build Squirrel Hall with staff and students. The building had no walls and consisted solely of a wooden roof suspended by tree trunks.

In the run up to our 125th celebrations, then President of The King Alfred School Society, Kara Conti, wrote a series of articles about the origins of the school and it’s early history. You can read them here:

October 1897: The Magnificent Seven

The King Alfred Founders

125 years ago this October a meeting was organised by seven Hampstead parents to discuss the possibility of founding a new school, co-educational, unattached to any religion, and taking into account the ideas of educational reformers and their realisation of individuality. Subjects would be interlinked, homework would not be set as leisure and play were deemed essential, and no scholarships or prizes would be worked for as learning for its own sake was

the aim.

These ideas had been circulated to the local community, and interested parties were invited to this meeting to discuss a curriculum and an educational ethos for a school that would be very different to anything on offer at the time. The meeting led to the foundation of a Society and, the following year, a school.

As present President of the King Alfred School Society, which was surely born that night, I have been researching the seven pioneering parents to whom we owe everything.

Isabel White Wallis (1853-1923)

Isabel, along with her friend Alice Mullins, was very much the driving force behind the movement. Married to a scientist she believed in a rational approach to education. She encouraged discussion of a wide range of views in the press and questioned many contemporary values and practices. She was once quoted as saying, “By means of examinations and other aids, children are ground in a mill where individuality is repressed and where humanity is minted into pieces as like each other as the coinage.”

I found her grave in Hampstead Cemetery and the remarkable sculpture of her there allowed me to look into her eyes and somehow capture her spirit.

Alice Mullins (1847-1920)

A sculptor, married to a sculptor, she worked closely with Isabel to bring their ideas to fruition. She was passionate about artistic freedom and the cultivation of individuality. The very first meeting of the seven took place in her studio.

Frederick Waldron Miall (1857-1934)

A journalist and author, he acted for the first few years as chairman. His extensive range of press contacts served the propagandist aims of the group well.

Cecil Sharp (1859-1924)

Cecil was a musician, composer and folk song collector. At the age of 23 he emigrated to Australia where he taught, composed and conducted in Adelaide. He returned to England in 1892 and taught music in a preparatory school in north London. He became Principal of

the Hampstead Conservatoire of Music in 1896.

Gerald Maberley (1871-1961)

Gerald was a barrister at law and gave invaluable service to the group, fulfilling the role of Honorary Treasurer. He was the longest serving founding member. He lived at 1 Ellerdale Road; the school would later open at 24 Ellerdale Rd, Hampstead.

Godfrey Hickson (1854-1932)

As a solicitor he was of great service in drawing up all the legal documents in the formation of the Society and the Articles of Association. He lived at 20 Ellerdale Road at the end of his life.

Hamo Thorneycroft (1850-1925)

Hamo was a sculptor enjoying a high degree of success as a leading exponent of the New Sculpture, a movement in British sculpture reacting against the neo-classicism of mid-Victorian sculpture. He received public commissions for statues of Oliver Cromwell and Alfred the Great and was knighted in 1917.

What united these seven parents was the drive to provide a better education for their children, but not only that. They were determined to create a demonstration school that would have a long term impact on the world of education. What a brave gang.

Kara Conti, President of the King Alfred School Society

1898: The New Century Society

125 years ago this month our founders decided against the name The New Century Society and opted for The King Alfred School Society instead. They planned the opening of their brave new school for 1898 which was approaching the 1000th anniversary of the death of King Alfred the Great. Nationwide plans were already in place to celebrate this king, one of only two monarchs ever given the title ‘the Great’ and a ruler perhaps best known for his attitude to learning. He founded a school at his court and educated his daughters as well as his sons. He invited scholars to assist him to translate works from Latin to English to facilitate learning for all.

Our founder, Hamo Thorneycroft, a celebrated sculptor, was commissioned to create a statue of King Alfred at this time. The magnificent bronze stands to this day in Winchester, Alfred’s capital. I found this photo, credited to John Brimfield, of Hamo with a plaster cast of the statue. It stands a striking 15 feet tall but looks even more towering in this print with the sculptor standing in the background.

As President of what might have been the New Century Society I cannot stop researching this piece of history. My latest research has revealed more about those first families. That foremost founder Isabel White Wallis (nee Callard) had three nephews also enrolled that first year. Her family, the Callards, were bakers and confectioners. Who remembers Callard and Bowser toffees or butterscotch? It was an enormously successful brand in my childhood.

Kara Conti, President of the King Alfred School Society

February 1898: The KAS Society Logo

Another date to celebrate in this 125th year!

In February 1898 the Arts and Crafts designer and architect, Charles Voysey, one of our first parents, delivered the design for the logo of the Society. We have lived with this beautiful logo for the Society ever since but how often have we looked at the detail of it?

Happily Voysey left a note describing the ideas behind the design. Central is the tree of good and evil springing out of the heart. He depicted Alfred with details drawn from early manuscripts, notably in a crown copied from an image of the later King, Edgar. On the King’s left is a monogram taken from a coin minted in 880AD in Alfred’s reign. The monogram is formed by the letters of Londonia (London).

On the reverse of the coin there is an image of Alfred in profile and around it the letters AELFRED RE. Voysey used some of the lettering in the logo from the coin but strangely not all of it. The L is missing and the F is not fully formed. That’s a little mystery.

A non-religious, secular school?

King Alfred is holding The Bible in his right hand indicating Proverbs chapter 2 verse 6 which reads “For the Lord giveth wisdom: out of his mouth cometh knowledge and understanding”. How odd to find a Bible quote in the logo of a school whose founders were so intent that no religion be taught to their children. Another mystery.

What is true is that Alfred was an ardent Christian, known for his zeal and ability to convert Vikings to Christianity. His other great passion was education and learning, which is why the founders had chosen to name the School after him, not least because he educated his daughters as well as his sons.

Perhaps we need to look more closely at Charles Voysey himself. He was not one of the seven founders but enrolled his children at the School from the earliest days. Charles was the son of a Church of England priest who had educated him. Interestingly his father had been dismissed because he disagreed with certain accepted beliefs, for example he refused to preach the church’s doctrine on eternal damnation. He formed his own church, Theism, breaking free from the constraints of his previous role.

What did the founders think when they first saw the design, one wonders? There is no record of any dissent (that we have found yet!) but it is significant that the next design produced by Voysey for the school lacked any religious references. It was for a stained glass window for Ellerdale Road, the first School building. The V&A has this watercolour of the window design. No biblical quotes just the simple Latin motto ‘ex corde vita’ – ‘out of the heart springs life’. We wonder whether the original window is still there. Who is going to knock on the door of number 24 and politely enquire?

The Voyseys remained a part of the School for many years. The eldest son, also called Charles, became an architect like his father. He was latterly called Charles Cowles Voysey as he took his wife’s surname as his own middle name upon marriage. It was this Charles Voysey who drew up plans for the School at Manor Wood, beautiful buildings that sadly had to be exchanged for used army huts when the move was made due to a severe lack of funds.

Charles F.A. Voysey is known to this day for the many beautiful and distinctive houses he designed. Have a look at Annesley House, 8 Platts Lane, Hampstead. He built this for his father and it is where his father, the erstwhile C of E priest, died.

Kara Conti, President of the King Alfred School Society